‘A History of the Flute: IV,’ by Trevor Wye

This article was originally written for the British Flute Society in 2016 and has been shared with the permission of the author, Trevor Wye.

Theobald Boehm’s newly designed metal flute was first shown in 1847. In 1849 Giulio Briccialdi suggested an addition and alteration to the thumb key making it easier to play Bb. Then there were about two or three years of relative quiet while everyone digested Boehm's controversial flute, not only its keywork and new fingering system but the change in the bore which was now cylindrical with a tapered head. This was a radical difference as it changed both the tone and the performer's impression when playing it.

Then the fun begins… In 1850 Richard Carte's new flute appeared; in 1852 Richard Rockstro's conical adaptation of Boehm's flute was shown; in 1852, Robert Sidney Pratten's Perfected Flute made its appearance; in 1855 John Clinton's Equisonant Flute appeared; in 1858 Rockstro's first cylindrical flute; 1866 Carte patent Carte and Boehm Systems Combined, known as Carte's 1867; in 1870, John Radcliff's flute and in 1885 Maximilian Schwedler's Reform Flute. And so it goes on…

Confused? So were the flute playing public. It depended on whom you studied with, or which player you most admired as to which model of flute you might end up playing. These new models were either attempts to retain the old fingering where the F# was played with the 1st finger of the right hand or a refusal to accept the larger toned and somewhat louder cylindrical bore or perhaps it was a dislike of the use of metal instead of wood.

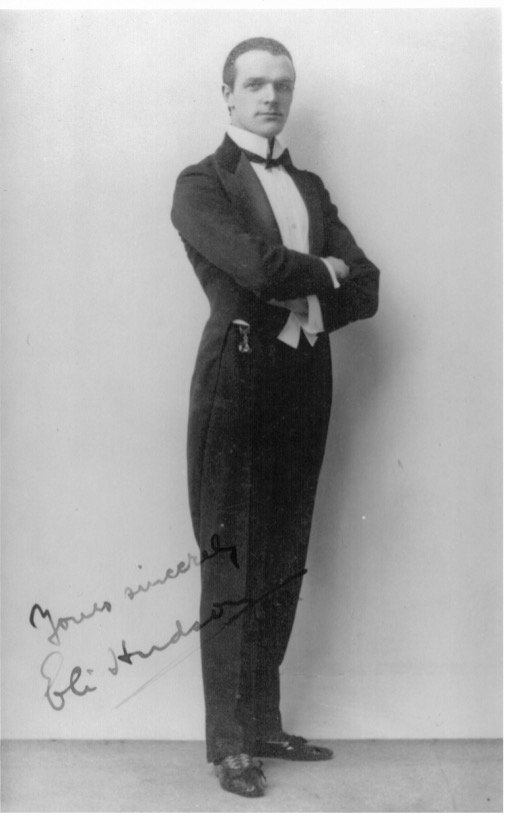

Looking at all the alternatives to Boehm, in 1867, came the best of them all, Carte's 1867 Model, subsequently used by several notable players. Amongst them were Winnie and Eli Hudson, who later, were amongst the first to play flute and piccolo solos on the new recording machines. The wall thickness of the silver tubed version of 1867 was usually of 'ten thou', that is ten thousandths of an inch in thickness, quite thin compared to our flutes of today which are between 14 and 18 'thou'.

Eli Hudson

The features of the 1867 flute are that it is similar to a Boehm flute in that it has Boehm’s cylindrical bore of 19 millimetres and follows his idea of large, evenly spaced tone holes with all open-standing keys. Its difference is that it has a different fingering system, one that some believe is the best yet devised. It removes most of the difficulties of the Boehm flute, such as moving from E to F sharp as it had two touch-pieces for the right hand 1st finger, one for F # and one for F natural, so that in a sharp key you simply used the F sharp right hand button. Even though F sharp is now available as a first finger right hand note - as on the simple system flutes - you can still play F sharp with the second finger of the right hand as on the standard Boehm flute of today, too. The all-fingers-off 'open D' is particularly useful in some quick passages, and the fingering as a whole is rather easier in the upper register. This system was far from rare: Rudall Carte sold as many of these as they sold standard Boehm systems until the 1880s. Some leading players used 1867 flutes, including W.L. Barrett, the professor of flute at the Royal College of Music at the end of the nineteenth century. The 1867 system was still in professional use as recently as the 1980s, played by William Bartlett, first flute in one of the BBC orchestras. It is pure conjecture to speculate that, had the 1867 model appeared before Boehm's 1847 flute, it might have become the flute we all play today.

What of the rest of the world? During the mid to late 19th century, most of the notable French players had adopted the Boehm system, as had the Belgium players. Only in Germany, did some players steadfastly refuse to be seduced by Boehm's design, mainly due to one man, Maximilian Schwedler. Schwedler, born in 1853, lived most of his life in Leipzig. Was he stubborn? Did he have good reasons for holding out for so long? Yes, he maintained that there were subtleties of expression which were not available on the Boehm flute: more than that, he preferred the tone of the simple conical bore flute, a view that some of today's historically inspired players have sympathy with. There is decidedly a difference in tone quality. Schwedler had already familiarised himself with the Boehm flute in Amsterdam and admitted in later life that he admired it, but he always played on his own variety of the simple system' flute'. Not only did he play on it but he insisted that his many pupils also adopt this system.

Schwedler was an important player, giving first performances of some of our best known works. Brahms wrote to him after hearing him play his Fourth Symphony, telling how much he enjoyed his playing. One would have thought that Wagner too would have enjoyed the Boehm flute's big tone but he referred to it scathingly as a cannon!

Schwedler started off with the standard 8 keyed flute and was an energetic man, constantly improving his flute adding keys and improvements, aptly naming it the Reform Flute, even changing the shape of the lip plate. Schwedler vigorously objected to the use by composers of the fourth octave, saying that the piccolo was the correct instrument for these notes. Even in 1935, he still insisted that the Reform Flute was the best flute. He died in 1940 at age 87.

It is surprising how one man can change the course of our history, but that's what Schwedler did in Germany. In modern times, the tone of the flute and of players worldwide is gradually merging and becoming similar in quality resulting in a kind of 'uni' flute tone. Only because of history's 'oddballs', like Schwedler, do we keep some individuality and originality.

By 1920, the large majority of German players had finally succumbed to the wonders of Boehm.

Due to this huge rise in popularity of the flute, there were flute offshoots such as the Walking Stick Flute, which was just an extended plain wooden one-keyed flute with a metal tip and a stout handle at the top. Some models were even furnished with a thin sword blade inside the bore which could be drawn out from the head joint end. Another even had an umbrella attached to the foot end too, just in case you might be practicing in the rain with the added security of being able to defend yourself in case of attack! If you think that is odd, just think about the special bowler hat which had a mechanism inside it; when the wearer approached a lady in the street, he would nod his head and the hat would automatically rise up clear of the scalp. In all probability, the lady would faint clean away.

Walking-Stick Flute/Oboe by Georg Henrich Scherer ca. 1750–57 (The Metropolitan Museum)

For those who preferred to play the flute vertically, Boehm made the drawing below as a speculative idea which has seen a modern equivalent now widely available.

(Ludwig Boehm)

Giorgi, an Italian, patented the ebonite flute shown below which employs all of the fingers of each hand and both thumbs. The other upright head joint below that is an experimental one made in the 1950s by Rudall Carte and formerly owned by Geoffrey Gilbert.

(Author’s collection)

(Author’s collection)

Then there was the extraordinary Chevalier Rebsomen, who having lost part of his arm in battle, had a single-handed flute made for him which rested on a support which was screwed to a table top.

There was a big increase in the number of people playing the flute which resulted in a great deal of new music. Frederick Kuhlau who was a concert pianist, wrote a large number of flute solos with and without accompaniment and many fine duets, trios and quartets including the excellent Quartet in E for four flutes. Caspar Kummer's trios for three flutes are amongst the very best as is Eugene Walkiers' Quartet in F# minor for 4 flutes. It was for the performing pleasure of the players that these pieces were written though for public performance Khulau and Kummer also wrote chamber music works for 2 flutes and piano as well as flute, viola and piano. Kummer and Ignaz Pleyel wrote more than a dozen full length quartets for flute, violin, viola and cello.

Robert Pratten was one of the many English flute players who dabbled in inventing new key systems and in tuning the flute to new scales in our past. It is a curious fact ‑ often commented on by foreigners ‑ that this tradition has carried on to the present day. In London, there have been more flute performers (as opposed to makers) experimenting with their flutes than anywhere else in the world. Amongst them is William Bennett, who continues to experiment with scales and headjoints; Elmer Cole, former principal flute of the Saddlers Wells Orchestra who has, behind the scenes, been influential in flute scales and the late Sebastian Bell, an enthusiastic experimenter as well as Alexander Murray, former principal flute of the LSO and many others, including your author, who all found messing about with flutes totally irresistible.

Robert Sidney Pratten was born in 1824 in Bristol into a musical family. He had help learning the eight keyed 'simple system' flute from his family when he was young and at the age of twelve was playing solos in public. He also played the viola left handed and the piano. In 1845, at the age of 21, he became principal flute in the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. A rich and generous baronet, Sir Warwick Tonkin took him on tour in Europe to give him the opportunity to see some of the world and give him the chance to play in the major European capitals which he did with great success.

On his return, he changed to the Siccama System flute, another keywork system, though such was his skill that it didn't matter what kind of flute he played. His only objection was having too many extra keys on his flutes. Whilst pursuing his career in London, he composed a great deal for the flute, though much of his music has been forgotten. According to the author R.S. Rockstro, he was 'one of the most generous, amiable and warm hearted of men'. His performing career earned him the respect of his colleagues and of the public, who were enthusiastic in their praise of him. In 1852 he began his experiments on the keywork and fingering system which later resulted in his 'Pratten's Perfected' flute, and this was manufactured by Messrs. Boosey & Co. He died in Ramsgate in 1868.

Seen below is the Lot flute formerly owned by Paul Taffanel which was bought for him by Louis Dorus, his teacher when he was a student.

Louis Lot No.600 owned by Paul Taffanel (Author)

The entry below in the Louis Lot Company account books for November 1861 reads: 'A cylindrical flute of silver with an embouchure of gold'. The author has played the Taffanel flute on two occasions and it had a very sweet tone, underlining the reports about the great master's tone. According to Marcel Moyse, Taffanel considered top B as the highest note the flute should play, disliking any higher notes as of poor quality and unusable.

Louis Lot, the famous French flute maker probably made the first gold flute, No 1375 in 18K gold flute in 1869. It was subsequently owned and played by the eminent French flutist, Jean-Pierre Rampal.

Flutes were made of other metals besides silver, the most popular being nickel silver, an alloy of copper, zinc and nickel. It was said to have been invented in Germany, hence its alternate name, German silver, due to its resemblance to silver and in France, it was reinvented again under the name, Maillechort, said to have been named after the two Frenchmen who 'invented ' it, but, in fact nickel silver was already in existence long ago in China as paktong metal.

The classic nickel silver flutes made by Louis Lot, Lebret and Bonneville, amongst others, were made of an alloy containing 6.7 percent nickel. After about 1900, perhaps because of the greater use of it in electrical components, its formula was changed to about 19 percent nickel. It is thought today that this change made the flutes less responsive. This was about the same time that seamed silver and nickel silver tubes were made which many believe also might have influenced the flute tone. The seamed-tube flutes of these French makers are highly sought after for their special tone today. They were made by cutting a length of sheet silver to an exact width and placing the sheet lengthways between two rollers which resembled the clothes mangle or wringer of former days, shown below.

The sheet was rolled under great pressure, the result of which action is that it rolled in on itself forming a tube. The two sides were then hard-soldered together before being worked on and made into a perfect cylinder. Around 1900, a method was found to make seamless tubes which many believe that the flutes were less responsive when this new technique was introduced.

Emil Rittershausen (1852-1927) was a Boehm flute maker who trained under Boehm and Boehm's partner Carl Mendler in Munich. He too made a gold flute which he presented to the Tsar of Russia, Nicholas ll who in turn gave it to Emil Prill, the German flutist in his court orchestra in the late 1880s.

Kurt Gemeinhardt studied flute making under Rittershausen and then emigrated to the USA where he founded the company of that name.

Meanwhile, during the rest of the century and into the 20th, there were several newly pitched flutes such as piccolos and flutes in Db used for the military bands, flutes in Bb and A -wrongly named tenor flutes - alto flutes in G and bass flutes in F and C. The rise of interest in flute bands, especially in Northern Ireland, also encouraged new pitches which Rudall Carte and the Potter company were able to fulfil.

Gradually, the new key system madness quietened down as players almost universally adopted Boehm's 1847 system with only a few players still playing the 1867, the Radcliff and the Siccama systems.

The rise in popularity of the French teachers such as Paul Taffanel, Philippe Gaubert and Marcel Moyse was due not only to their warmer playing with its use of vibrato, but also to the regulated system of study they developed in finger technique, tone and articulation which was also evident in their performances. Similarly, in Italy the prominent teachers there, Emmanuele Krakamp and Rafaele Galli wrote many studies, exercises and pieces. In Germany, there were also great makers and composers too. In this list we must include Joachim Andersen, born in Denmark in 1847 who worked in Germany for many years before retiring back to Copenhagen. He wrote some of the most beautiful and intelligent flute studies ever written, such as the 24 Studies, Opus 15. Paul Taffanel said of these: 'They are comparable to the études of Chopin'. Indeed they are.

© Trevor Wye 2016