‘A History of the Flute: V. To the Present Day,’ by Trevor Wye

This article was originally written for the British Flute Society in 2017 and has been shared with the permission of the author, Trevor Wye.

In this final part, the focus of attention will be on the influential players at the turn of the century and later, as these had an impact both on development of the flute and its literature.

Eli Hudson was mentioned in the previous part as a player of the 1867 System and he was the most extraordinary piccolo player you may ever hear. Eli - pronounced Ee-lie - was born in 1877. He studied at the Royal College of Music with A.P Vivian and W.L. Barrett (another 1867 player) and later became principal flute with the London Symphony Orchestra. Eli Hudson formed a Trio with his brother and sister, Elgar and Olga, who were very popular as a stage act before 1914. They recorded many salon pieces, but it was as a piccolo soloist that Eli Hudson is remembered by enthusiasts the world over. He had a sweet singing sound which made one forget that the instrument was so small and his technique and tonguing were amazing too. He made many piccolo records with orchestras, military bands, and with the piano, that it is difficult to know which is best. He can be heard, together with other historic soloists on this useful and helpful website compiled by Robert Bigio in association with Christopher Steward: http://www.robertbigio.com/recordings.htm

Eli Hudson (Robert Bigio Flutes)

"All my life, I have loved and admired him; he is and will remain a symbol for all flute players present and to come," so said the famous Marcel Moyse about his teacher, Paul Taffanel. Moyse was also one of the most celebrated players of the 20th century, and it reflects the respect that so many flutists felt for Taffanel whose influence was enormous and resulted in his being known as The Father of Modern Flute Playing.

Taffanel was born in Bordeaux, France, on the 16th September 1844 and gave his first public performance before the age of ten. When the family moved to Paris, young Taffanel began lessons with Louis Dorus, who later became the professor at the Paris Conservatory, and then he joined Dorus' class where he was awarded his Premier Prix, an important diploma, after only a few months of lessons. On the completion of his studies, he toured, giving concerts in several countries and then decided to take up conducting as well. He was appointed Professor of Flute at the Conservatoire in 1893.

In the 19th century, flute players liked to play airs and variations, a simple musical form, but one which the musical public got tired of hearing. Taffanel wanted to get away from this form and encouraged composers to write a better class of solo for our instrument. Some of the great French composers, such as Faure and Gounod, either wrote pieces for Taffanel, or gave the flute an important solo in chamber works, usually with him in mind. He tried all his life to raise the level of our repertoire and encourage players to perform more intelligent music and he succeeded: today, we have several fine solos from French composers, largely as a result of his work and influence.

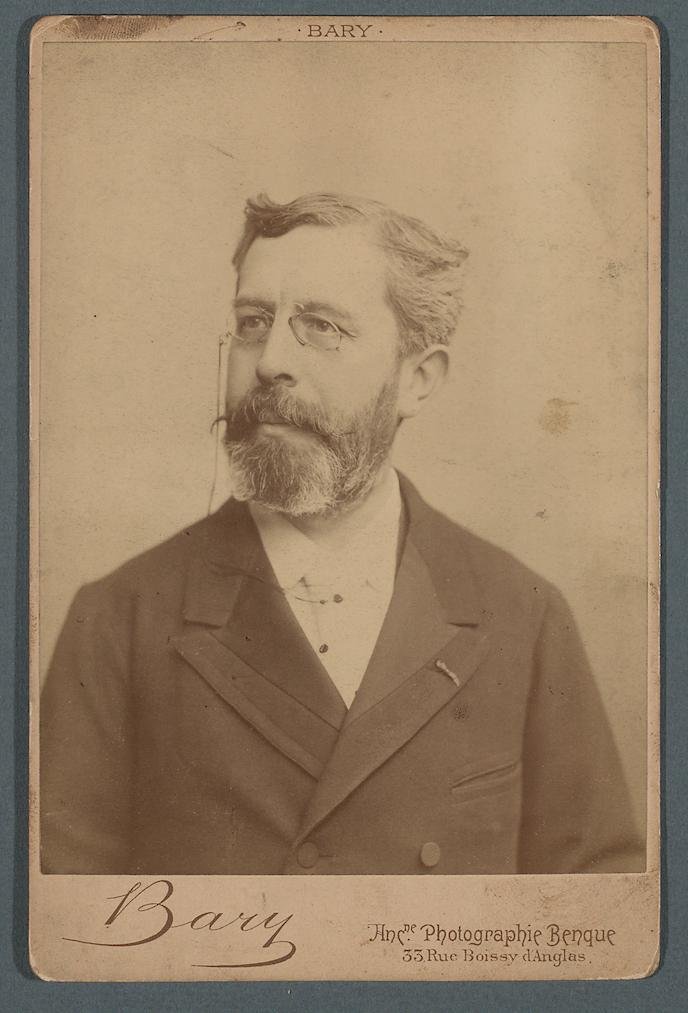

Paul Taffanel (Library of Congress)

It was Taffanel who suggested to the Parisian flute maker, Djalma Julliot, a way to make top E easier to play: close the second of the G keys, the one not touched by the finger, and so the split E was born. As a teacher, he was inspiring and taught his pupils to think intelligently about practising, a legacy which continues to this day. But as a performer, his playing was said "....to be a revelation. Just imagine: flute playing that was intelligent, cultured, and above all, musical ‑ something unheard of before"

About the year 1904, Joachim Andersen, the famous composer and flute player, visited the Paris Conservatoire where Taffanel was teaching and asked if he could listen to his class. Taffanel asked Andersen if he would allow him to play one of the best known of the 24 Andersen Studies, No.3 from opus 15. After he had played, Andersen commented, "I didn't know I had written such beautiful music!" What a compliment. Marcel Moyse was present at that class and said that he remembered that performance all his life. Camille Saint‑Saëns, wrote to Taffanel after he had retired, "The terribly sad thing is that you will no longer play the flute, and that no one will ever again play like you". Taffanel died in Paris on the 21st November, 1908.

Thus began the great reputation that the Paris Conservatoire gained through the succession of teachers who followed Taffanel such as Philippe Gaubert, Marcel Moyse, Fernand Caratgé, Gaston Crunelle, Jean-Pierre Rampal and later, Michel Debost and Alain Marion. Part of the Conservatoire's reputation lay in the fact that composers were commissioned to write for the examinations, resulting in a number of important pieces in our repertoire.

French players were better known, but in the rest of Europe, there were also many noteworthy players who influenced our repertoire and mechanism. In Italy, Giulio Briccialdi (1818 - 1881) and Giuseppe Garibaldi (1833 – 1905) were both prominent players whose literature, especially studies, are still extensively used today. More recently, Severino Gazzelloni (1919 -1992) for whom Pierre Boulez (Sonatine) and Luciano Berio (Sequenza) wrote major works, also played jazz. Germany's Karlheinz Zöller (1928 – 2005) was principal flutist with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra for more than 25 years.

Meantime, Georges Barrère had emigrated to the USA in 1905 to take up a post in the New York Symphony Orchestra taking with him Taffanel's teaching and performing legacy and from him sprang a line of renowned players including Joseph Mariano, William Kincaid and Julius Baker. It was William Kincaid who bought the first platinum flute, made by Verne Q Powell, in 1939, a flute he played throughout his life.

Albert Fransella was the first to play a solo at the Promenade Concerts, just before 1900, playing The Waltz from the Godard Suite, but as you can see below, he came to a sad end.

(Author’s collection)

Oddly though, the UK was slow in adopting the expressive tone of the French and still clung to the straight-sounding tone of players such as John Amadio, Robert Murchie and others. It was Geoffrey Gilbert in the mid-1930s, who asked a recording company why they were employing the Moyse Trio in London to record instead of the local players. The producer's reply was, 'You should listen to them. They sing'. As a result, Gilbert attended a Moyse Trio recording session of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos and it influenced the rest of his life. Even though he was himself an established London performer, he decided to study with a French player, René Le Roy, to acquire their ways of articulation and vibrato.

Geoffrey Gilbert became known as the Gentleman of the Flute, such was his reputation as a polite and kind man. He was born in Liverpool in 1914 and after studying at the Royal Manchester College of Music, joined the renowned Halle Orchestra at the age of 16 as Principal flute, and then the London Philharmonic Orchestra when he was 19. He taught at Trinity College and the Guildhall School of Music in London, and though he was highly regarded as a player, it was as a teacher that most flute players remember him today. He was one of the first to adopt the silver flutes common in France, as most British players used wooden flutes at that time. Of course, eventually, we would all have changed to the French style, but Geoffrey Gilbert was the first courageous man to try it. In the process of change, he learned a great deal about his own playing and teaching and this helped him to help others. The list of his former students reads like a who's who of the flute world and includes William Bennett and Sir James Galway.

Geoffrey Gillbert (Robert Bigio Flutes)

He had a fine sense of humour as you will see below by his list of flute problems with the prices for 'Dr. Gilbert' to fix them.

(Author’s collection)

At 8.15 one morning at a summer school staff breakfast, hearing someone say that had heard Gilbert practising his scales that morning, the author asked if this were true? He sighed, put down his knife and fork, and said, 'There are certain daily functions which are part of my morning routine, and include washing, showering and shaving. Practising my scales is one of these daily activities. It is not a subject for public discussion'.

That just about sums him up.

He had a flute made for him as the newspaper cutting below shows:

From the Daily Mirror, September 1st, 1950 (Author's collection)

Gilbert played an open G# flute which influenced some of his pupils to take up this option, William Bennett amongst them. He died on May 18th, 1989.

Born on 5th July, 1879, Philippe Gaubert was born into a musical family, studying music with his father and at the age of seven, went to Paris where he had flute lessons with Paul Taffanel's father, later studying with the great man himself. He studied both the flute and composition at the Paris Conservatoire, and at the age of 25, became a professional conductor. Increasingly, he spent less time with the flute and more at composition and conducting, though he was appointed Professor of Flute at the Conservatoire and only retired from that post in 1932 in favour of his friend and former pupil, Marcel Moyse. It seems that Gaubert was not too interested in practising later in his life. He was said to have gone from his bedroom to his study in the early morning, taking up his flute, and attempted to play top A extremely softly. If it sounded good, he wouldn't practise that day! But he did practise hard in his younger days. He was the dedicatee of several of our important repertoire pieces for flute and piano. He died in Paris in 1941.

At the turn of the 20th century, a notable addition to the flute was the Brossa F#, an idea created by Jean Firmin Brossa, a Swiss player who studied in Paris, moving to the UK to become principal flute of the Halle Orchestra in 1870. It is a spatula-shaped key just above and at right angles to the RH third finger key. It pushes down the F# key without pushing down either the cups of RH 2 or 3. For a closed hole flute, it gives a superior quality F# in both octaves. The key is arrowed below.

Brossa F# key on the RH keywork (Author)

In the late 19th century, the French flute makers thought that it was both be better acoustically and easier to manufacture, if all the keys, particularly the Gs (3rd finger LH) were in a straight line, an 'inline flute'. Many now believe this was a mistake as it has led to some acquiring left hand tension problems. Better acoustically? A glance at the flute will confirm that there are several keys not inline, amongst them, the G keys, thumb keys and foot keys rendering that theory nonsense.

Open holes were introduced by the French makers to emulate the older style flutes and it was also said to encourage a good hand position. Later, it was said that 'open hole flutes make a more open sound' - more nonsense. If this were true, at the present time we have five good 'open' notes and a dozen bad 'closed' notes. If a particular open hole flute sounds better, perhaps it is because it is a better flute?

Foot extensions to low B, Bb and even A were known in late 19th century and into the 20th in Italy with surviving examples. The low B key, with the addition of a 'gizmo' key allows the B key to be lowered without lowering the low C or C# keys and which helps with the emission of top C. One Japanese maker has recently revived these extra low note extensions as, although they may not be used much, they do influence the remainder of the compass.

Top E, F# and G# were always problem notes and one was fixed by the 'split E' mechanism, suggested by Taffanel. A more modern idea to improve top E is the addition of a donut, a plastic ring or disc inserted into the tone hole of the second of the two G keys, the one not touched by the finger. Unfortunately, though it does help top E a little, it spoils the tone of the two A's, lower and middle. In effect, the player has improved one note and spoiled two others. When the insertion is very small, it has less effect on the two As.

There is also the split F# mechanism, an expensive addition involving two key cups, one on top of the other in the left hand, but it does make the F# easier to emit. Then there is Albert Cooper's idea of half closing the thumb key when fingering G#3: a lever is attached to the G# cup which connects with the thumb key. Most makers now offer the G/A trill key and the C# trill key in various forms. Rollers on the foot keys too, were common in the 19th century and have been added to various foot keys.

The Brögger Mechanik was invented about 30 years ago, but is, in fact, a reinvention, the principal having been used on flutes at least as early as the 1920s by Rudall Carte and Co. Brögger's mechanism is very much improved and has a smoother feel than the R&C version. Its principal is to lower the F# key without a rod passing through the whole RH mechanism. The normal mechanism uses pins to lock the parts together. The Brögger Mechanik connects the third finger RH key to the F# key externally and is known as 'pinless'.

As mentioned in the last part, many larger and smaller sizes of flutes were made in the last century. The bass flute too, is still the subject of experiments, with attempts to make it louder. Contra-alto flutes sometimes appear, an octave lower than the alto, and contrabass flutes of various shapes and configurations are often seen in large flute choirs.

At each international flute festival or convention we can see 'improvements' offered in lip plate style and shape, corks and stoppers, shaped keywork, sound bridges, additional keys and other bits to add on. There have been extensions and additions to the foot joint as well. Sometimes the proposition may be seen by some to be an improvement, though so often it is a passing fad and leaves you, the player, a little poorer. All the same, everything new is worth a try.

The material from which flutes are made is becoming increasingly diverse. Gold and platinum of various mixtures and 'bondings' of metals, a kind of metal sandwich, are more common now. Besides various combinations of gold and silver, the makers, trying hard to be innovative, have mixed in titanium, germanium and palladium. Stainless steel, aluminium and bronze have also been used and there has been a marked rise in the number of wooden flutes now being made.

Albert Cooper was born in 1924 and his reputation and influence was worldwide, creating flutes of the highest mechanical excellence, establishing alterations and additions to the keywork of traditional flutes, but more famously, to their scales. The term, Cooper’s Scale has become part of our flute talk.

Albert Cooper

Cooper worked in such a straightforward way, with basic handmade tools and uncomplicated explanations. Flute makers for many years had enjoyed an almost sacred reputation, not completely deserved, of knowing all there is to know about their art. Cooper's use of a severed tree trunk, a hammer, reducing rings and a strong arm showed that anyone could make headjoints if they chose. On his retirement, he looked at the collection of a lifetime’s tools on his bench and said, quite accurately, ''Flute making tools? It’s really just a pile of old junk''

Cooper’s lathe operated by a treadle

His engineering skill was incredible because he worked to great accuracy which is why his flutes played so well and were admired as pieces of engineering excellence.

Elmer Cole and William Bennett both contributed to Albert’s search for a true scale on which to build our flutes and were in fact largely responsible for the calculations which resulted in what became known as Cooper’s Scale. As ‘the Scale’ developed and players offered their opinions, Cooper updated his figures and gave the latest revision to anyone who asked for it. Over time, he gave different scale figures to different makers. Just a few years ago, he said: ‘Cooper’s Scale? What’s that? There isn’t ‘a Scale'. There is a constant revision taking place so that, at any one time, there is a set of figures which you can use to design your flute, but these will change in the light of experience. I altered the scale a little as the years went by, mostly according to certain criticisms leveled at it. I now feel that I have more or less reached the end of the road scale-wise.’

A couple of days after Albert’s 80th birthday, he was asked, ‘You are such a famous man. There is hardly a flute player anywhere who hasn’t heard the name of Albert Cooper.’

‘Well,’ he commented, ‘I dunno why. All I’ve done all my life is tinker about with flutes…’

After some years of experimenting and working with Albert Cooper, Alexander Murray, then principal flute of the LSO, designed the Murray Flute prototype which was first built in 1960 by Cooper, though underwent some modifications in later years. For the Boehm flute player to understand just one part of this key system, both the third and little fingers of the RH are put down to play low D. If only the third finger was lowered, it plays D#. It follows that the Eb key cup is automatically raised for E, a great help. It followed on from Boehm' principal that when fingers are lowered, they play lower notes. In 1972, a number of Murray flutes were manufactured by the Armstrong Company in the USA, but the idea didn't really catch on. We saw the same problem with the 1867 System: It was an interesting keywork design but after players had already changed systems, a new one would have to have big advantages to tempt the majority to take to it.

Eva Kingma a Dutch flute maker, has introduced the Kingma System flute which is basically the same as a Boehm system flute with a C# trill and has all the normal keys and standard fingering but its difference is the addition of six extra keys allowing the performer to play the missing quarter tones which are not available on the normal flute. This flute addresses the demands of composers and players who not only wish to play quarter tones but allow the performer to temper and fine tune the regular notes and to play glissandos too. As we discovered before, alto and bass flutes have been in use for several hundred years, but Kingma, together with Bickford Brannen makes a speciality of new designs to enable the instrument to sound less like an asthmatic hippopotamus. The so-called Kingma & Brannen altos and basses are very interesting to play where they address all the problems of the first few notes of the second octave and the tone of the third. More recently, they announced the Matusi-head joint, a membrane head joint which changes the tone, somewhat after the Chinese Dizi, and a new design of trill keys on the Kingma contrabasses. They suggest there will be another surprise next year!

Each country produced well known and influential players, too numerous to mention, some of whom suggested improvements to flute makers. Jean-Pierre Rampal was an outstanding performer having had a 50 year career in both playing and publishing little-known pieces and inspiring new works. Sir James Galway's meteoric rise to fame has also widely contributed to the popularity both of the flute and its repertoire and, like Rampal, becoming one of the first players to establish a solo career on the flute. His name has become a household word amongst players. William Bennett too has been very influential and whose career has recently been celebrated by the BFS.

This is not a who's who of players as so much information can be found online, though mention should be made of some of the non-classical players such as Herbie Mann, known as the Pied Piper of Jazz; Matt Malloy, whose traditional Irish music on an eight-keyed flute is legendary. The extraordinary Robert Dick too has been very influential both in promoting flute innovations and by encouraging composers to create new techniques and sounds for us to learn. Non-traditional players who should be mentioned are Pannalal Ghosh, the wonderful Indian bansuri player and later, Hariprasad Chaurasia, and Georges Zamfir who popularised the pan pipes both in Rumania and worldwide.

Finally a look at a fun instrument the author built a few years ago using a Chinese 'Perspex' plastic flute, the underside of which is pictured below. It has a built-in 9v battery and about 40 Ultra bright coloured LEDs connected by around 8 metres of wire, which brightly light up the inside of the tube in six different colours. This is achieved by a number of magnet operated and/or switches attached to the keywork so that, as a note is changed, so does the tube colour. See it on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=itJf0Gv0pyc

Colour-change flute (Author’s collection)

After all the centuries of workmanship and creativity throughout the whole world, our instrument is still fundamentally just a whistle with bits added on.

The English name 'flautist' comes from the Italian flautista but isn't it better to adopt the more sensible name, flutist?

A friend was at a formal dinner sitting next to a rather regal lady who asked him, 'What do you do?'.

'I am a flautist, ma'am'.

She turned away to speak to the person seated on her other side for a time, then turned back to ask him, 'What exactly is it that you do with floors?'

Perhaps we should also adopt a collective noun for large gatherings of flutes or flute players, first suggested many years ago by the English flutist, Fritz Spiegl.

Not a 'Flute Festival, Flute Fair, Flute Carnival, Fiesta of Flutists, a Flute Meeting', a Jamboree, or even a 'Flute Convention' - but an Afflatus of Flutes and An Afflatus of Flutists.

©Trevor Wye 2017